When children are playing and selecting what to do themselves, they become deeply engaged. While this is happening, the adults should be observing and waiting for a moment in which they feel they can make a difference. They should then interact to ‘teach’ the ‘next step’ as appropriate for that unique child at that precise moment. Each time they interact with a child, they are observing, assessing, planning for, and responding to, that individual child. Such interactions are the most important and powerful teaching moments.

The traditional cycle of observation, assessment and planning is recommended in numerous documents including Development Matters and The National Strategies document “Learning, Playing and Interacting”. In this document I wish to highlight the section that states:-

“Babies and young children …. are experiencing and learning in the here and now, not storing up their questions until tomorrow or next week. It is in that moment of curiosity, puzzlement, effort or interest – the ‘teachable moment’ – that the skilful adult makes a difference. By using this cycle on a moment-by-moment basis, the adult will be always alert to individual children (observation), always thinking about what it tells us about the child’s thinking (assessment), and always ready to respond by using appropriate strategies at the right moment to support children’s well-being and learning (planning for the next moment).” (Page 22 – 23)

This paragraph matches the planning system that I have been asked to write about in this article. A skilful practitioner knows that they need to observe before interacting with a child and they know that the best interactions are not planned in advance. Rather, as the quote above suggests, the best interactions happen when we respond to a child’s interests and efforts immediately. We can then record some of theses interactions afterwards. I would stress at this point that we should only record a fraction of the interactions that we have. We recognise that if a practitioner is writing, they are not interacting. Therefore we need to keep the recording to a minimum.

This is nothing new. This is just good early years practice. It is what an attentive parent does with their child and it is what practitioners have always done. However, I believe, as a profession, we have become governed by fear and a misplaced belief that we have to document everything and that we have to have physical evidence for all our judgements about a child. This fear and pressure has led practitioners to start devising “activities” that will meet a specific learning objective. We need to get back to basics – secure in the knowledge that children are “hard-wired” to learn and that we just need to facilitate and support this at each and every moment. However, this does not need ‘activities’ or written plans. So what then does this look like in practice?

I will give some general points as to the way the environment is organised, what the adults do and what the paperwork looks like. The ideas have been adapted in various settings to suit their needs. However, in all cases, the aim is to organise the setting - including the time, the resources and the adults - to ensure that the majority of the children display deep level engagement for the majority of the time. If that happens, then we can be confident that they are making good progress. Nearly 40 years of observing children has taught me that the best levels of engagement are seen when children have autonomy, when they truly have choice as to what they will do. Therefore, I would advocate that children are able to initiate their own play for as much time as is possible.

An enabling environment is critical. I use the term “workshop” to best describe what is on offer. When children arrive, nothing is set out but everything is available and accessible. The doors to the outside should be open immediately as some children can only become deeply engaged outdoors. From day one, the children should be supported to explore the environment to see what is available, to select the resources they would like, to use them appropriately and to tidy the area when they have finished. Ground rules are essential when so much freedom is given – all the children need to feel safe. Clear and consistent expectations are key. For example, indoors the children will walk and use quieter voices – running and shouting can be done outside.

To give a flavour of the environment, I have included a few photos. The main message is that the resources need to be accessible and flexible. In order to meet numerous different interests, it is easier to have one resource that can be used in infinite different ways, rather than dozens of different ‘closed’ resources. For example, large wooden blocks can become a car, a boat, a stage, a staircase. “Less is more” is a phrase I often use. Fewer, high-quality, open-ended resources are preferable to dozens of ‘single use’ items. Children are not then ‘pushed’ into following the adults’ agenda – rather their own ideas can be realised and supported. We don’t need to keep changing the environment – if it is engaging the children, then there is no need to change it.

Sessions should be organised to maximise the amount of “free-flow” time available. Thus, in a nursery for example, the children arrive, self-register and go off to play where they choose. All staff should support the children in their chosen activity – there are no focus activities. The adults go to the children – they don’t call the children to them. Just making this one change in the behaviour of staff can bring about a complete shift in emphasis and focus. The children become the focus instead of a particular activity that the adult has planned. About 20 minutes before the end of the session, the children should tidy up and come together for about 15 minutes before lunch or home time.

The weekly organisation is as follows:- On Friday, the staff select 10% of the group who will be the “focus children” for the following week. For child-minders, and in baby rooms, practitioners would select a larger group to be the focus. If some children only attend for a few hours a week, then they may remain as a focus child for a few weeks until their learning journey sheet is complete. These children are given a form to take home for their parents to complete – asking about current interests of the child, any special events in the family and any questions the parents may have. We also send home cameras with the focus children. The families take photos over the weekend and return the camera and form on the Monday. Settings that have an online system ask the parents to upload some photos from the weekend.

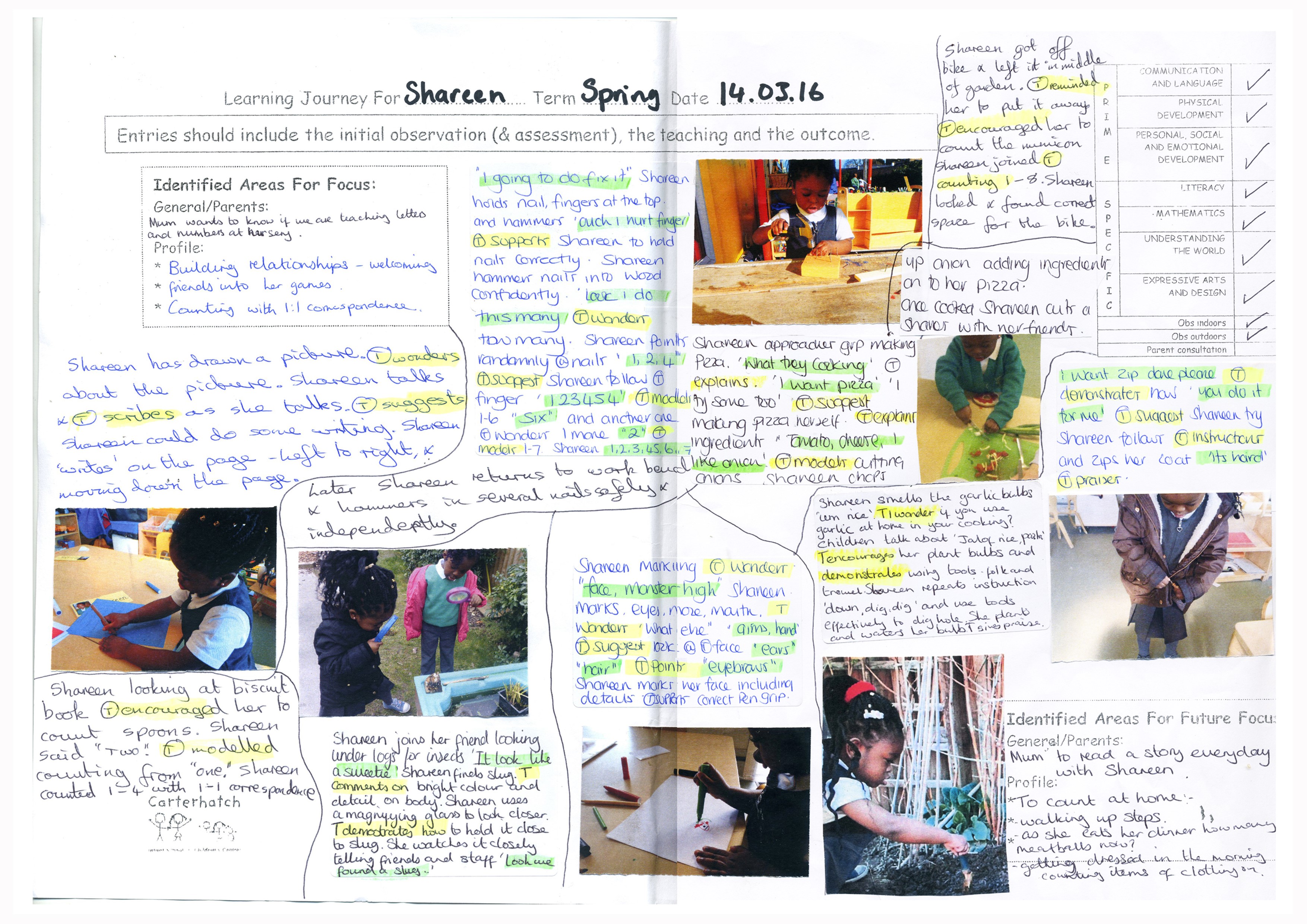

On Monday a “Learning Journey” sheet is put up for each of the focus children. These sheets are blank at the start of the week (except for a couple of words to indicate areas that the staff or parents would like to try and capture). During the week any adult who has a productive interaction with a focus child records the event on the learning journey. It is important that the whole cycle is recorded – i.e. the initial observation (& possibly the assessment), the teaching of the appropriate next step, and the outcome.

Examples (for children of various ages) might read:-

“Seray is on the verge of crawling. ‘T’ challenges her to crawl by leaving her favourite toy just out of reach. Seray is content to be on her tummy, and after a short while pushes herself up onto hands and knees. As she rocks forward, she is able to reach her toy.”

“Ethan wants to turn on the tap but can’t reach. ‘T’ shows him the step and suggests he could use that. Ethan pulls the step over, climbs up and turns on the tap.”

“Ross is struggling to use the tape dispenser. ‘T’ explains about the blade and models how to cut the tape. Ross listens and perseveres until he cuts the tape.”

“Jenna wants a turn on the rope. ‘T’ models the language and encourages Jenna to repeat the phrase ‘Can I have a turn please?’ Jenna does this and the pair then took turns independently”

“Omar is drawing a dinosaur but doesn’t know what the feet looked like. ‘T’ explores ideas with him and provides a tablet for Omar to use. Omar finds an image of the dinosaur and uses this to complete his drawing accurately.”

“Sienna has completed her story but has no punctuation. ‘T’ reminds her to read through her writing and explains how to use full stops. Sienna reads her story and adds full stops correctly.”

In all the examples above, the “plan” was formulated and delivered “in the moment”. In each case, the practitioner immediately identified a ‘next step’ and ‘planned’ how to achieve this in that moment. Thus, Seray learnt to crawl, Ethan learnt how to use a step, Ross learnt to use a tape dispenser, etc. In each case the interaction was uniquely suited to the child. There was no stress because the adult went to the child and observed them where they had chosen to be. They did not “hi-jack” the play with a learning objective that they had in mind. In each case, the adult went with the child on their journey. The words that are shown in blue indicate the ‘teaching’ that happened. The Ofsted definition of teaching is very useful to support staff in recognising the teaching that they are doing through their interactions and through the enabling environment.

“Teaching …. includes … communicating and modelling language, showing, explaining, demonstrating, exploring ideas, encouraging, questioning, recalling, providing a narrative for what they are doing, facilitating and setting challenges.” Ofsted September 2015

Entries on the learning journeys are often accompanied by a photo. The sheets are gradually filled up over the course of the week and become a wonderful individual record. Staff meet with the parents of the focus children in the week following their focus week. The discussion revolves around the completed learning journey – a truly individual picture of the child’s experience.

Just to clarify – the adults are interacting with all the children, but just recording interactions with the focus children. In this way, paperwork is manageable and ‘teaching’ time is maximised. Any “Wow!” moments are recorded for individual children and added to individual records – whether focus children or not. In many settings, such wow moments are still recorded on paper, but if an on-line system is in use, then this can be used for wow moments.

In addition, for children aged over 3, staff complete another sheet which is really a group learning journey to record any significant events that occur in the class and that involve a group of children. Again this sheet has been re-designed by many settings – essentially it contains the same observation cycle – observation, teaching, outcome. An example might read:-

“Group notice slugs. ‘T’ suggests children use magnifying glasses. ‘T’ demonstrates and explains how to use these. Children look closely at the patterns on the slugs.”

“In the moment” planning is a very simple idea – observing and interacting with children as they pursue their own interests and also assessing and moving the learning on in that moment. The written account of some of these interactions becomes a learning journey. This approach leads to deep level learning and wonderful surprises occur daily. When OFSTED arrive they usually ask “So what will we see in here today?” When planning in this way, the answer is “I have no idea!” and then the discussions can begin!

Anna Ephgrave

Anna is Assistant Head Teacher responsible for the Early Years at Carterhatch Infant School and Children's Centres. She has inspired and supported settings both in the UK and abroad. She now works part time as a consultant, both nationally and internationally.Edited by Rebecca

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.