Over time, through training, encouragement and support from my peers I grew in confidence and improved my knowledge and skills in this area of learning and now I know and understand what it is I am being asked to do. But what if you’re a new student and you have been asked to ‘do an observation’ for the first time? So, let’s start with the basics; What actually is an observation?

What is an observation?

When looking in the Oxford English Dictionary (2016) for the meaning of the word observation we are met with suggested definitions such as ‘monitoring’, ‘examining’, ‘scrutinization’ and ‘surveillance’. It makes it sound a bit like being a spy for a top government organisation! In more relatable terms, an observation is the opportunity to produce a factual account of actions, sometimes undertaken within a pre-set time frame.

In the world of early years, an observation can be described as an unbiased and uncritical method of ‘capturing the facts’ demonstrated by a child through their actions and speech (Sancisi and Edgington 2015, p.6). Bruce (2001) refers to an observation as being a ‘description’ that informs our knowledge and develops best practice. The Development Matters guidance (2012) refers to observation as ‘describing’. It is clear then that an observation should be an accurate description of what is being seen and heard (Bruce 2010). It should be contextualised (i.e. it should be clear where, when and why it is happening) and it should be focused on the here and now, “What you are seeing and hearing” and should not be subject to interpretation by the observer (Sancisi and Edgington 2015, p.7). According to Bruce (2001, p.126), “it should open up our thinking and never be used to control children’s play and learning.”

The Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) (DFE 2014, p.13) requires practitioners to observe children in order to “understand their level of achievement, interests and learning styles.” The observations should then be used to inform and shape future learning and development.

Now we have identified what an observation is let's have a look at why we do them.

Why do we observe?

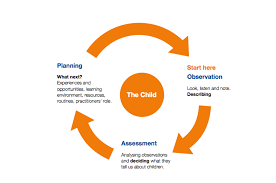

The Development Matters guidance (2012) refers to observation as ‘Looking, Listening and Taking Note’. Bruce (2005) suggests that it is not just enough to observe and gather information. She explains that the observation then must be analysed and interpreted in order to help practitioners evaluate the appropriateness of what they have provided. The act of observation is the beginning of a process that leads a practitioner into their assessments (of what a child can do and might be able to do ‘next’) and then, through reflection and effective practice this ultimately into their activity and environment planning (which will, in turn, encourage situations that can be observed, thus starting the cycle again).

Hutchins (1999) explains that the process of assessment to planning and back again helps practitioners recognise how children have been ‘affected’ by the learning opportunities provided. Linking assessment with evaluation and planning helps practitioners to be clear in their intentions, their actions and their consideration in planning next steps for the child (Bruce, 2005). This ongoing process is commonly referred to as ‘The assessment and planning cycle’. The EYFS (2012) Development Matters guidance refers to a cycle of Observation, Assessment and Planning that supports children’s learning and their current needs.

- The planning cycle – firstly, OBSERVE

Observation is a statutory requirement of the Early Years Foundation Stage (DFE 2014) but it is also an essential tool in understanding the development and the needs of the children in our care. According to Drake (2005), practitioners use observation to discover what children can do, the concepts and understanding that they have and their approach to learning. The Principles into Practice card 3.1 (2007) suggests that practitioners complete observations to find out the needs of the children, the interests that they may have and what they can do. It is also a method of recording children’s responses in different situations (DSCF 2007). Observation is a method of informing us about how children play and learn (Bruce 2001). To capture what a child is doing, not what they are not doing (Sancisi and Edgington 2015).

According to Edgington (2004) the use of observation is embedded in the constitution of what is defined as ‘effective practice’ in the Early Years. Practitioners need to be aware that making decisions about learning, without the use of observation, can lead to inappropriate learning opportunities that could cause an outcome of disengagement in its participants. Without observation, learning experiences would be planned based on what practitioners felt was important, interesting, fun or encompassing all three aspects, thus failing to address the needs of the children within the setting (Bruce 2010). The more information that can be gathered, the more effective the support mechanism and future learning (Siraj-Blatchford et al. 2002).

- The planning cycle – then, ASSESS

The Statutory Framework for The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) (2014 2.1, p.13) states that assessment is “an integral part of the learning and development process.” It is a judgement regarding the development and learning of a child and involves practitioners reflecting on a number of observations and then ‘analysing’ and interpreting the findings (Sancisi and Edgington 2015).

The EYFS (2012 p.3) Development Matters guidance refers to the practitioner identifying milestones within the theme of ‘A Unique Child’ and understanding where the child may be in “their own developmental pathway.” Sancisi and Edgington (2015) point to the danger of matching observations to the milestones in the guidance, taking the relevance and focus away from what is being achieved by the child. They feel that it is more appropriate to produce an assessment that is ‘relevant to the child’ rather than copying from a book, or list (Sancisi and Edgington 2015 p.11). Using Development Matters in this way is a concern shared by Nancy Stewart (2016), one of the authors of the document, who believes the use of Development Matters as a “tick list of descriptors of what children must achieve is limiting” children’s future learning and development.

There are different types of assessment that practitioners are can utilise to inform future learning and development. The most frequently completed type of assessment being the daily observations and notes made on children’s interests and abilities. This is also known as formative assessment, or assessment for learning. Bruce (2010) believes that this type of assessment is the most important as it is “informing future planning for the children concerned.”

Another type of assessment is summative, which is used to review, or give a “summary of children’s achievements so that their progress can be tracked” (DSCF 2007 3.1). The Statutory Framework for the EYFS (2014) requires practitioners to review children’s progress at the age of two and again at the end of the Foundation stage. The purpose of the two year old check is to identify strengths that a child may have and any areas where “progress is less than expected” (Early Ed 2014). The Framework stipulates that if an area of concern is identified, then a targeted plan must be put in place to support the child’s future learning and development. It must involve parents/carers and other professionals, such as the Special Educational Needs Coordinator of the setting, where appropriate.

The review that is required at the end of the Foundation stage is known as an Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP). It is completed in the final term of the year in which the child reaches age five and is a record of achievements for parents/carers, practitioners and teachers. The profile is a reflection of the ongoing observations, records and discussions with parents/carers. As Bruce (2010) identifies, summative assessment must be based on the observations made over time, by practitioners and parents.

According to the Statutory Framework (2014 p.14) the profile should demonstrate “a well-rounded picture of a child’s knowledge, understanding and abilities, their progress against expected levels, and their readiness for Year 1.” A Good Level of Development (GLD) is defined by the Government as achieving the expected levels in the Prime Areas of Learning and Development and the Early Learning Goals in the Specific Areas of Mathematics and Literacy. The levels are recorded by the use of a point system 1= Emerging, 2= Expected and 3= Exceeding. An overall score can be achieved by the addition of scores for all seventeen Early Learning Goals. According to statistics released by Department for Education (2016) the percentage of children nationally, achieving a good level of development has increased by 3 percentage points (ppts) on 2015 from 66.3 to 69.3 per cent (DFE 2016).

- The planning cycle – then, PLAN

Tassoni and Hucker (2005) understand that the planning cycle fails to be complete unless the previous records and observations are used to inform future learning and development. The use of observation as a planning tool is essential as “It enables the practitioner to plan for the individual child in such a way that they have a sense of belonging and a feeling of inclusion” (Bruce, 2005). By observing babies and children, the practitioner will be able to think more carefully about the opportunities provided by the environment and will be able to plan and manage for change (Dryden et al. 2007). According to Sancisi and Edgington (2016) the most effective plans are those that are created and executed in response to what is being observed. They need to be “acted on immediately” and “may never be written down”. Anna Ephgrave (2015) discusses the need for “Planning in the moment” where skillful practitioners to respond immediately to the learning opportunity. This ensures that the learning is ‘relevant’ and in a ‘real time situation’.

Sancisi and Edgington (2015) discuss having a number of observations in order to plan for future learning, or learning priorities. They suggest that changing the language from ‘Next steps’ to ‘Learning priorities’ helps practitioners identify more easily with the concept. The Development Matters guidance (2012) states that planning is necessary to challenge and “extend a child’s current learning and development.” Learning priorities, according to Sancisi and Edgington (2015) can include opportunities for children to “practice and consolidate their learning, extend their knowledge and understanding and encourage interest in other aspects, or choices”. This differs to the opinion of Anna Ephgrave (2015) who understand that by working “in the moment, Next steps are carried out immediately and without the need for recording. This means that the planning cycle is completed many times in one day, rather than the traditional practice of planning for future activities.

The Statutory Framework for the EYFS (2014) requires settings to record information to complete the development check at 2 years and the EYFSP but that is all, so why do we spend so much time making detailed accounts? Sancisi and Edgington (2015) understand that to achieve high quality provision, leaders and managers will have a clear overview of the progress being made by the children in their care. This is made possible through the recording of evidence and the collation of data over time, through observation. We observe to capture the facts of what we see and hear a child doing but actually how do we record the information in a succinct manner that is clear for all to understand? This brings us to the next section.

- How do we observe?

Sancisi and Edgington (2015) define three main types of observation, Informal, Participant and Focused. The observation can take many forms, dependent on the timescale and the intended purpose. Quick snapshot observations, or Participant observations as they are also known, are a more informal method of capturing moments as they occur. These are often on sticky notes and capture a moment as it happens, a significant development in the child’s learning. The observer may be involved in the session as part of an adult-led activity. More structured narrative observations, also known as Focused Observations that are planned and executed with an outcome in mind, can be used when more detail is required. The observer is usually at a distance and the children involved in self-initiated learning (Sancisi and Edgington 2015).

Time sampling and tracking observations are useful when more analytical data is needed as they provide a more visual account of proceedings. Observations can be made of individuals or groups of children, dependent on the focus. With groups of children the method needs to be more organised, using observation techniques that allow for conversations and actions taking place all at the same time. Observing several children at one can be useful when trying to gauge engagement in activities or the dynamics of the nursery session. For example, you may notice that certain activities or areas of the setting remain under used, whilst other areas prove more popular (Tassoni and Hucker 2005). Observations using a scale such as Sustained Shared Thinking and Emotional Well-being (SSTEW) or Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS) may be useful tool to measure engagement and interaction, between children and practitioners within the setting. Observation by electronic recording is becoming more prevalent as we embrace technology and utilise the benefits that it gives us, such as being able to capture moments instantly in a visual format and the sharing of information with parents and carers more readily. As with all methods of recording, the data produced must be monitored by leaders and managers to ensure reliability (Sancisi and Edgington 2015).

When is the time to observe? Is there a right or wrong moment? How does it fit in with an already busy session?

- When do we observe?

Opportunities for observing can be planned, if intending to look at a specific area of learning, patterns of behaviour or a child during a particular focused activity. According to Drake (2005) it is also important to be ‘constantly ‘tuned in’ to children’s learning’ and take opportunities to observe children as they arise. Bruce (2015) identifies that a narrative observation should be planned within the setting timetable, to avoid unnecessary interruptions and should be approximately 4-5 minutes in length.

There are chances to observe children as they interact in everyday play and during planned and unplanned activities (Early Ed 2014). Observations need to be taken in a selection of different situations and contexts in order to build a more holistic picture of the child (Bruce 2015). The Development Matters guidance suggests that “It is also important to learn from parents what the child does at home.” The Statutory Framework (2014) requires us to provide a partnership between the practitioners and parents/carers and discovering information about the child at home allows us to build a complete picture of the children in our setting. The child is at the centre of everything we do and it is our job as practitioners to ensure that the children in our care reach their true potential and we can only do this by really knowing them.

- Who are we observing?

We are looking at all children within our setting to ensure that we have an accurate view of their learning and development at any given time (Sancisi and Edgington 2015). Observation is at the heart of good practice and as reflective practitioners we need to understand the process so that we are confident in our knowledge and skills. Training and development in this area helps us to understand how and why we are observing children and the approach that it may take.

References

Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R. and Bell, D., 2002. Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years. Norwich:Crown Copyright.

Bruce, T., 2001. Learning Through Play. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Bruce, T., 2005. Early Childhood Education. 3rd Edition. Oxford: Hodder Arnold.

Bruce, T., 2010. Early Childhood: A Guide For Students. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

Department for Education, 2014. Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage. Runcorn: Department for Education.

Department for Children, Schools and Families, (DCSF), 2008, The Early Years Foundation Stage: Principles into Practice Card No. 3.1, Nottingham, DCSF Publications.

Drake, J., 2005. Planning Children’s Play and Learning in the Foundation Stage. London: David Fulton Publishers Ltd.

Dryden, L., Forbes, R., Mukherji, P. and Pound, L., 2005. Essential Early Years. Oxon: Hodder Arnold.

Early Education, 2012. Development Matters in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS). London: Early Education.

Edgington, M., 2004. The Foundation Stage Teacher in Action. Teaching 3,4 and 5 Year olds. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

Ephgrave A., 2015.. The Nursery Year in Action: Following children's interests through the year. Oxon: Routledge.

Harms, T., Clifford RM., Cryer D., 2014. Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS-3). New York. Teachers College Press; 3 edition

Hutchins, V., 1999. Right from the Start: Effective Planning and Assessment in the Early Years. London: Hodder and Sloughton.

Tassoni, P. and Hucker, K., 2005. Planning Play and the Early Years. 2nd ed. Oxford: Heinemann.

Oxford Dictionaries, 2016. Definition of Observation in english. Oxford University Press. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/observation [Accessed 27 October 2016].

Sancisi, L. and Edgington, M., 2015. Developing High Quality Observation, Assessment and Planning in the Early Years, Made to Measure. Oxon: Routledge.

Siraj I., Kingston D., Melhuish E., 2015. Assessing Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Sustained Shared Thinking and Emotional Well-being (SSTEW) Scale for 2-5-year-olds provision. London. Trentham books, IOE Press.

Stewart, N., 2016. Development Matters: A landscape of possibilities, not a roadmap. Early Years Foundation Stage Forum. Available from: http://eyfs.info/articles/_/teaching-and-learning/development-matters-a-landscape-of-possibilit-r205

[Accessed 21 November 2016].

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.